The Church of the Virgin and Child (originally St Peters until the fresco was found in 1888)

The Church of the Virgin and Child (originally St Peters until the fresco was found in 1888)

This church is one of those hidden places that go deep back into history, how far? we may never know, but amongst the numerous finds around the area there is a neolithic axe head, celtic coins and roman remains.

Canfield has been settled for a very long time, it is served by the River Roding, and it seems that the small streams that abound in this area converge near the Norman church. Behind the church is a Norman Motte with an outer bailey, both of which remain, the church is surrounded by a deep ditch, with the river running to the north of the church, water surrounding it on both sides.

Essex countryside, picturesque houses as you wander through narrow winding lanes, the church substantial amongst the small hamlet it now serves is fundamentally a manor church.

On the exotic tymphaneum cloistered behind the porch doors, are depictions of Odin and his ravens, show a Norse influence in its sculptures, the decorative fylfot crosses are fascinating, but the 13th century Romanesque mural, uncovered in 1888 is also extraordinary, here a sensitive artist has been at work. There is fine scrollwork of vine leaf above the fresco and the masonry lines are painted as well on the wall, red and yellow ochre are used.

The 13th Century mural of the Virgin and Child

The 13th Century mural of the Virgin and Child

Right hand pillar of the tymphaneum with Odin and serpents?

It has the 'dot' all down the serpent back, as seen on the Avebury font serpents. The tails are fanned out similar to a fish tail

The legend goes that the world serpent with his tail in his mouth was doomed to lie in the ocean encircling the world till the Ragnarok. Should the tail ever be pulled out of the jaws, universal calamity would follow. Brian Branston - The Lost Gods of England

Odin with the ravens Hugin and Munin and the Fylfot 'swastika' crosses

Odin with the ravens Hugin and Munin and the Fylfot 'swastika' crosses

Odin and the left hand raven, see note on the ravens of Odin

the Norman Tymphaneum, the central half moon motif though typically Norman style seems to represent the sun

the Norman Tymphaneum, the central half moon motif though typically Norman style seems to represent the sun

Note Odin's Ravens; Odin sends them out at dawn to fly all over the world and when they return, they sit on his shoulder and speak into his ear all the news they gathered.

20. O'er Mithgarth Hugin

and Munin both

Each day set forth to fly;

For Hugin I fear

lest he come not home,

But for Munin my care is more

From:

Grímnismál, The poetic Edda, 13th century.

Translated by Henry Adams Bellows, 1936

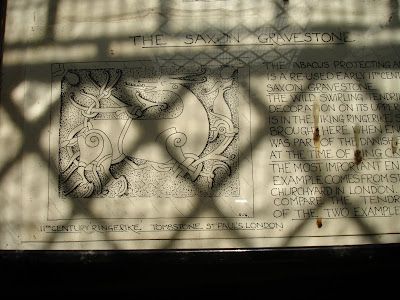

There is an interesting reuse of a 11th saxon burial stone in the Norman archway to the chancel.

It is difficult to see because it is used on top of the pillar of the archway, and has to be viewed upside down with a mirror. The Anglo-Scandinavian style is given as Ringerike, and is rather undistinguishable as a zoomorphic animal.

The Domesday book (1085) gives Ulwine, a great Saxon thane owning the estates around here at the time of the Norman invasion. And one wonders at the Scandinavian burial stone belonging to an invasion at the time of Cnut/Canute.

Cnut invaded Wessex through Kent at first but then went on to fight the English who were under the leadership of Edmund Ironside, Ethereal the Unready's son at London. A last battle at Assandun in Essex resulted in a victory for Cnut. The battle is said to have taken place at Ashingdon in 1016 on the south-east side of Essex, and the church there commemorates this victory.

Pillaging and minor battles must of course taken place through this part of Essex and maybe the Scandinavian burial stone at Great Canfield is the gravestone of a warrior that was killed at this time.

Whatever, this church is remarkable in its detail of the Norman tymphaenum and the two pillars decorated in Norse style, Odin a god of the North decorating a Christian church, though how the stories were intermingled is now perhaps lost. History recorded in stone only reveals a partial truth, but this church with the reuse of Roman bricks and a Scandinvian burial stone has some fascinating secrets.

Note; According to the handbook, the gravestone has a speculated date of 1050, which rather puts my theory out, the Norman invasion happening in 1066 of course, and the explanation of the two 'ravens' is that they are christian doves on either side of God. Feasible but given that there are two serpents on the other pillar with fish tails as illustrated by Branston and that this following report also follows the same line of thought that the carvings are of rare Norse origin....

Particularly like Great Canfield with its Odin carvings. I'd suggest a Danish influence here, rather than Norse (there are few Odin references in Norwegian place names. They're much more common in Denmark and southern Sweden). I'd expect more pagan symbols in Essex than anywhere else in the south-east. It became a Danish kingdom under kings Anwynd and Oskytel shortly after 878. But whereas Guthrum, who took over East Anglia, was baptized in 878, Anwynd and Oskytel are not mentioned as having joined him in baptism. It would seerm, therefore, that Essex remained under pagan rule somewhat longer. Essex already had a Saxon tradition of Christianity, of course - and, in your pic, we see the fusion of the two cultures. (Be careful when reading modern books on this subject. So many modern historians include Essex in East Anglia. But Guthrum had split up from Anwynd and Oskytel at Exeter the previous year. Essex was a separate Danish pagan kingdom until c.896). We get a lot of this stuff in NE Yorks. Here, we had Danes settling on the Wolds, and Norse settling round the edges of the Moors about ten miles to the north. They didn't get along - the Danes fought two battles with the Norse for control of York. So now we're left wilth a hotch-potch of Anglo-Irish-Danish-Norse symbolism - pagan symbols on Christian crosses, Christian symbols on pagan gravestones, and so on. I wrote a book about it once, but nobody wanted it. Every publisher or agent I wrote to said the same thing : fascinating subject but too specialized for our catalogue. In the end, I just threw it in a drawer and forgot about it. I liked your horse too. It's always depicted looking backwards - we don't know why. There's a good one at Lythe, just north of Whitby (which is markedly Norse, so the symbol seems to be common to all Scandinavians or it wouldn't also occur at Canfield) with a wrestling scene behind it - we don't know the significance

Stumbled across this blog post whilst doing my own research for my own blog. Good set of information on here! I had totally missed the saxon era gravestone inside, so I had started to presume the Odin and ravens (came to that on idea by my own conclusions) were included because the church was built on an ancient grove.

ReplyDeleteCome to think of it, it being the site of a smaller battle during the Canute rulership makes sense. Sites known for their use by Canute like Canewdon, Canvey Island etc, all have the 'can' suffix.

Obviously its unlikely to ever be verified - but I think this is the most likely explanation to be honest.